Why Batching is the Future of Food Delivery

Only batching can unlock a step function change in price

By all accounts, the future of food delivery looks bright. Thanks in part to the pandemic, food delivery sales have skyrocketed in 2021 and over the last few years.

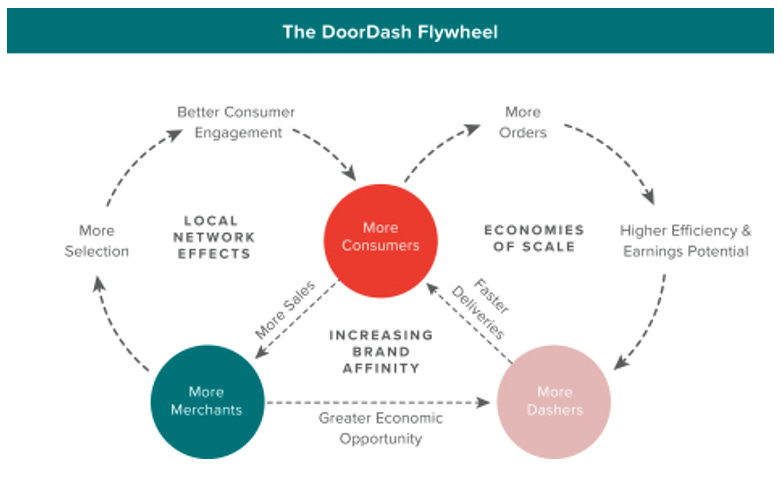

This long bull market has been driven by the introduction of three-sided delivery marketplaces: companies like Doordash and Uber Eats have created a lot of value by connecting consumers, restaurants, and couriers. These marketplaces are relatively reliable and can deliver a wide selection of options in <45 minutes. And they have brought delivery costs down significantly by creating efficient courier networks, meaning most orders can be delivered for $5-10 of fees (including tip). I can say from experience, having worked at Uber Eats, that the flywheel below (taken from Doordash’s S-1) is real and effective at enabling this marketplace.

And yet, all growth eventually comes to an end without more innovation. To quote Eugene Wei's famous essay (and risk sounding cliche for all of tech twitter), every company faces an "invisible asymptote." Eugene defines this as:

Invisible asymptote: a ceiling that our growth curve would bump its head against if we continued down our current path.

With food delivery, there's a good chance we are closer to the asymptote than many think. I'm not sure exactly when that will be (COVID has certainly changed things), and that doesn't necessarily mean delivery companies as a whole will see slowing growth given they are branching out into new verticals (convenience, alcohol, grocery, etc.). But when it comes to "traditional" food delivery, we should start thinking of new delivery models if we really want to ever get it as price competitive as cooking.

Why?

The main reason is that delivery marketplaces are still largely stuck on the model of one order-one courier. Couriers demand the market wage for their services (ex: $15-20 an hour). At 3 orders per hour, this means they need to get paid $5-7 per delivery. Let's say you wanted to get that down to $2 an order– then couriers need to be doing 8-10 orders per hour. This is a simplification (see appendix for more details) but close enough for this piece.

When courier marketplaces start up, it’s relatively easy to increase utilization and orders per hour as the flywheel (above) starts spinning. But at some point, you hit a wall. There are fixed costs to each trip (getting to the restaurant, waiting at the restaurant, dropping off the food) that can only be reduced so much. Given where people live relative to the restaurants they order from, I’d be surprised if you can reduce the average delivery time below 20-25 minutes (capping average deliveries per hour at 2-3). And utilization can't be close to 100%– reliability would decrease as fewer couriers are available to take new orders, leading to longer wait times and a higher percent of unfulfilled orders. Without relaxing the constraint on one courier-one order, you are pretty limited in your ability to meaningfully reduce costs once a marketplace matures.

Batching orders together works! In theory...

Unsurprisingly, this is pretty similar to the problem ridesharing has faced. With one rider-one passenger, solo rides' prices can only fall so by much. The answer to this blocker was "shared rides" (though the jury is still out on its success).

Similarly, I think the answer in food delivery is "batching" multiple orders together. The idea isn't totally new. Some companies in fact already rely on batching orders with a "shared rides" type model today (ex: Postmates Party, Uber Eats), but it seems like they only account for a small % of orders and the vast majority of food deliveries likely still operate with the one courier-one order model.

Consider how important this type of batching is to basically any other type of delivery operation. Imagine if every time you ordered a single item on Amazon, they sent one truck filled with just your item to deliver to your home. That’s effectively the state of food delivery in the US today!

But batching on-demand is probably not feasible

So is batching the silver bullet that food delivery needs to continue its fast growth? Not for the "on-demand" (unscheduled) orders we see today. In order to batch orders together, you need a lot of things to go right (Footnote 1). You need them to:

1) Come from the same or nearby restaurants

2) Be ordered around the same time

3) Be dropped off at similar times

4) Be dropped off in similar locations

And the shorter the time window available to batch, the harder it is to find orders to match together. For reference, (last I checked) Uber Eats has a 5-minute window where you can batch your order only if you choose certain restaurants.

Satisfying these constraints today requires a lot of “liquidity” in your marketplace. In other words, you need a lot of orders in a geographic area to have high batch rates. Unfortunately, it does not seem like marketplaces in the US today have nearly the liquidity needed to reliably batch on-demand orders together. That’s not to say they can never get there — China seems to be close, as its high density and significant # of orders mean couriers can juggle “more than half a dozen orders at once” during peak hours. But in the US, I expect it will be very challenging.

“Hot” food makes things even more difficult

Batching is hard enough on-demand for any product, but there’s another huge constraint when it comes to food delivery: hot food. Everyone is familiar with the experience of ordering a pizza and having it be cold by the time it arrived. Unlike other delivered products (ex: Amazon package), most food delivery orders today are a ticking time bomb which must be delivered within a relatively tight window, regardless of whether someone has a wide dropoff window (ex: 7-9pm) or a small one.

There will always be unpredictable hiccups during delivery (courier can’t find the apartment, restaurant finishes cooking too quickly, elevator is broken). But with hot and perishable food, you have almost no room for error. Each hiccup means all the following deliveries are late and cold, which means refunding the customer, pissing off the restaurant, and possibly churning both. The risks rise exponentially as batching increases, as you just need one hiccup to mess up the whole chain of orders.

Maybe having all couriers use specialized bags to keep food hot is a solution, but it’s not clear to me how effective these can be at solving the problem.

Scheduling & reheatable food makes cheap delivery feasible

So batching for on-demand, hot food may be too hard to pull off in significant numbers. We need a system where you can increase the batch rate and extend the item quality window (potential dropoff time). The only solution I can see is having orders scheduled with reheatable food.

Scheduling ahead of time (say by 5pm for a 7-8pm dinner dropoff) can massively increase the batch rate. Going from batching everyone ordering within a 5 minute window to a 2 hour window has the same effect as increasing your city's density by 24x (120/5)! With scheduled orders, you can preplan routes and group orders together by building/area (Avo is an example of how building level delivery is done for groceries).

But given the constraints we've discussed from delivering hot food, the food being delivered also needs to be reheatable or cold. Unlike many meal kits options today, I think this food would require minimal work for the end customer, since it would just involve a simple pop in the microwave.

These two changes could make batching much more viable and significantly reduce the cost of delivering food. And while I've focused on the delivery side, there's also the other cost of ordering food: preparation and cooking. That could (and may) be its own blog post to write, but I'll note that a system of scheduled and reheatable orders would reduce these costs too. Co-located ghost/dark kitchens which bulk cook reheatable meals should be cheaper (and more amenable to batching) than ordering food from a traditional restaurant.

Mealpal is an interesting example here: they require all pickup orders many hours in advance with no customizations, allowing existing restaurants to bulk prepare and cook. As a result, they are able to charge $6 a meal instead of $10.

Do customers want scheduled, reheatable meals?

I'm reasonably convinced that, logistically, batching can work well for scheduled/reheatable meals. But what I'm less convinced of is how much demand there will be for this product even at a lower price for two main reasons.

First, how many customers view scheduling as worth the hassle?

People are notoriously undecided about the “whether,” “when,” “what,” and “from where’s” of food delivery. I know I often don’t decide until the night of whether I’m going to order in or not. If someone gave me the option of a $2 delivery fee if I locked in my order by 4pm and a $6 delivery fee if I order on-demand at 7pm, I’m not sure how often I’d pick the former.

Interestingly, this is a problem most rideshare companies have faced too: getting riders to schedule their rides or take shared rides without large subsidies has always been a challenge.

Second, will reheatable meals ever taste as good as freshly cooked ones?

The sad truth is that most reheatable meals suck today and I haven't had any experience that has changed my view so far. There are also some types of foods for which reheating obviously just won’t work very well (ex: Pizza). One solution some have tried (like Tavola) is pairing a smart oven with delivered recipes to improve quality control, but I haven't tried it and this adds another layer of complexity and cost.

I will acknowledge that in many ways my argument is a blast from the past. Munchery, Sprig and Maple all tried versions of this concept and all failed. From the outside, it seems like the demand was there and the quality was high (I remember loving Maple's food). Instead, the issue was that they just couldn't make the economics work and reduce the actual cost of food prep + delivery to manageable levels. More companies have popped up to try this, like Freshly (acquired by Nestle for $950m) and CookUnity (Series A startup in New York). I can only speak to CookUnity, which has impressed me but still feels overpriced for the food quality I'm getting and the inconvenience of ordering 3 days ahead with not many options.

The opportunity ahead for 3p marketplaces

This is where I believe current food delivery marketplaces like Uber Eats and Doordash have an opportunity. They've largely solved the logistics side in a way that the Munchery/Sprig/Maple's of the world failed to. They also have the tech to create efficient batching of scheduled orders, and the existing liquidity right off the bat.

I’m not exactly sure how this will look, but I think these marketplaces should focus on building the platform for scheduled/reheatable meals. They should have products dedicated to these orders and could partner with existing restaurants or create partnerships with new delivery-only brands. There could be a separate section of the app focused on scheduled orders with a clear value proposition to customers (cheaper!), and maybe a subscription service along with it.

These marketplaces would benefit from the wide variety of restaurants and cuisines willing to plug into the scheduled orders ecosystem. Unlike the limited options of a Freshly or CookUnity, imagine having hundreds of options for your set of dinners each week!

There are lots of ways to pursue this and I’m excited to see more innovation in this space. Email me at charlesrubenfeld@gmail.com if you have any thoughts on this topic.

Thanks to the following people for their feedback on this piece: Brandon Trew, Rob Deaborn, Adam Stein, and Ari Baskous

Footnotes

(1) To simplify things, I ignore partial batches like having a courier pick up two orders and deliver them to different locations (ex: one 10 min away and one 25 min away).

Appendix:

Let’s recap the drivers of food delivery costs: The cost of food delivery can be broken out into food (cost to prepare) and non-food (cost to deliver). Most of the cost of a delivery today (the latter) is the cost of paying the courier, whose hourly wages cost are determined by the prevailing market wage/gig-economy opportunity cost, such as driving for Uber during peak times (comparable to other low-skill jobs). This hourly wage is mostly a function of time with some minor adjustments (a courier may be ok making $15 an hour for one order but may demand $18-20 an hour if they are delivering complicated orders, or are working at busy times). So the courier cost per meal looks something like this:

Now you can see that meals delivered per hour is crucial to delivery cost. If a courier can only deliver one order per hour, your single delivery may cost $15. Today, couriers can deliver multiple orders per hour, and marketplaces have increased the number by both reducing non-utilized time (less time waiting around) and reducing on-trip time (better matching/routing, reducing time for couriers to get to restaurants). There is more marketplaces can do here, but much of the low hanging fruit is gone IMO. This leaves the number of meals per delivery as the most important factor driving costs lower in the future.