Being at a Top VC Firm Matters More Than You Think

How venture is different than other asset classes and why it matters

Venture capital is unique. Unlike investors in other asset classes, venture investors don’t fully control the companies they invest in. Instead, the companies choose which VCs they want to invest. An investor could do all the research in the world and be 100% sure a startup is going to be extremely successful, but there’s a good chance they can’t get access to invest in the deal in the first place if they aren’t at the right firm.

Coming from a public markets background (macro), this was pretty shocking at first. In these markets, you don’t need anyone’s permission to buy Apple stock, USDJPY, or US Treasuries. Whether you work at a top hedge fund or live in your mom’s basement, you can just go on your computer and click the buy button. Predicting the future is sufficient for being a great investor, regardless of your sales skills.1

In most investments, if you want something more than the next person, you can just offer to pay more and you’ll get it. But in venture, price is not as important for who wins each venture deal. Given the option between a Tier 1 investor (ex: Sequoia) at a $50m valuation and an investor no one has heard of at a $100m valuation, most startups would choose the former.2 It’s not that price doesn’t matter at all, but venture is not about selling to the highest bidder. All other things equal, startups are willing to accept lower prices if it means getting the “right” investors on your cap table.

Venture capital is private investing, not public, so that can explain some of the differences. For example, private equity3 is also less price sensitive than public markets and isn’t purely about selling to the highest bidder. But based on conversations I’ve had with friends in private equity, price is still way way more important as to who wins the deal than in venture. Offering 5% more than Blackstone or KKR can win you the deal in PE even if you aren’t a name brand firm.4 Even if access to deals isn’t universal in these markets, it’s much better than early stage venture where many deals are not even shared beyond a very small group of investors.

Venture is different for good reason

It makes sense why venture is like this given the transactions are not “exits.” In public markets you are selling something once and you just want to maximize the price. In other private markets, like private equity, companies are often selling majority stakes or 100% of the business, so maximizing the price also makes sense. The seller may in theory want a great firm to continue their legacy, but it’s not as important as how much money they are making on the deal.

But in venture, especially early stage, your fundraise is just one of many future fundraises you’ll likely do. Founders are selling minority shares of their business and, unless they are selling secondary, are not making any money from the fundraise itself. Getting investors who help you get to the Series B is more important than optimizing the price of your Series A. The more early stage you go, the higher the signaling value of having a top-tier investor is for 1) recruiting employees and 2) getting other investors in that and future rounds. There are other benefits like portfolio operations, talent acquisition, etc. But I'm closer to Vinod Khosla’s view that most VCs are not adding a lot of value in their advice/help to startups, so I think the majority of the value is from signaling.

Venture has other unique incentives to avoid maximizing price. Accepting a higher valuation from a worse firm could mean less dilution today but a higher risk of your next fundraise going poorly because you are being valued at an above market multiple. You also discourage employees who think there is less upside to their equity if you are marked too high.

These facts make “be better at picking assets and just pay more for them” a strategy which is not viable for non-top venture funds even if it can work for non-top firms in other asset classes.

Being at a top fund matters much more in venture

I think the implications are more important than most people realize. Venture’s unique dynamics mean the firm you join is way more important than in any other industry or asset class, and the data backs this up. If you are at a Tier 3 venture firm that does not have the same access as a top firm, it’s very challenging to generate good returns.

This might sound banal to some. Who doesn’t want to work at the best firm in whatever profession they are in? And I agree! It obviously makes sense to try for Blackstone/KKR if you’re in PE or Pershing Square if you’re in L/S equity. But my point is that it’s simply not as important for generating strong returns and being successful as it is in venture. Some of the best equity hedge funds I know are small ones you have never heard of and just drive alpha through very strong research processes. Private equity is littered with less well-known firms that generate strong returns and win deals over the big giants.

The data supports this as there is more “persistence”5 in venture capital returns than any other asset class. If your last venture fund was in the top quartile, there’s a ~50% chance you’ll be in the top quartile in your next fund.6

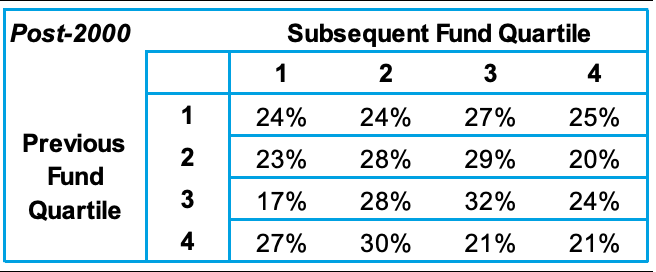

This isn’t just because venture investing is private. Private equity funds don’t show the same persistence since 2000 and being in the top quartile last fund has no predictive power over the next fund. This dynamic holds even more so for mutual funds and most hedge funds strategies too (ex: only 0.72% of all active US mutual funds had finished in the top quartile every year from 2016-2020).

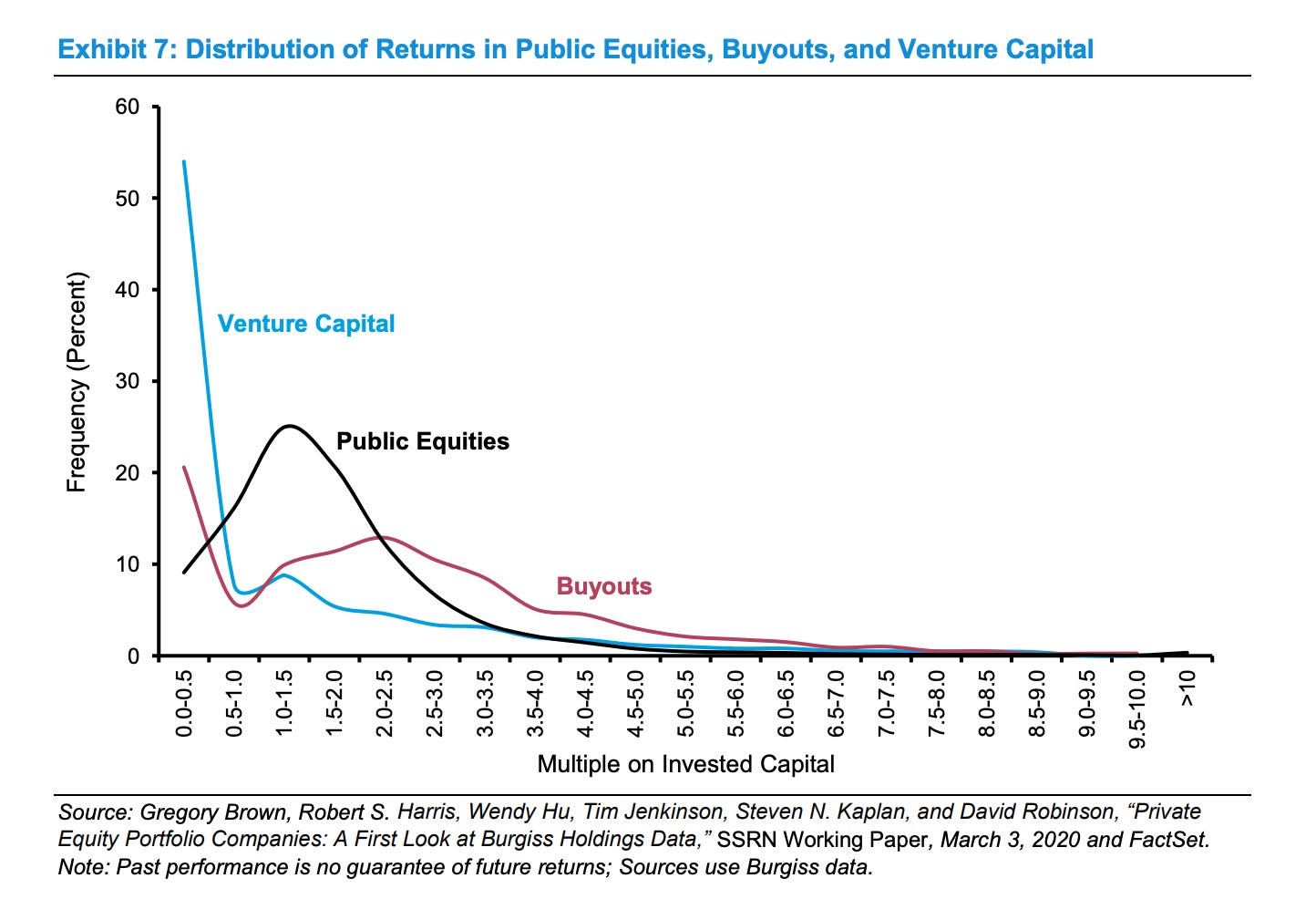

The other issue with VC is that fund returns dispersion is so wide that many funds earn nothing at all. The power law doesn’t only exist in venture portfolios, it exists among venture firms too. Being top quartile in VC means making insane annualized returns (20-80%), but being bottom quartile means negative returns and no carry.

5% of 0 is still 0

I don’t think enough people trying to get into VC take this idea seriously enough, especially if they come from a tech background. If you want to work in big tech and couldn’t get a job at a FAANG company, getting a job at a smaller tech company is still often a good deal. Maybe you make a little less, but you could get a lot of upside and still be successful. The same holds in finance. Many Tier 2 banks are worth joining if you don’t get the Goldman offer, as are many Tier 2 PE firms or hedge funds.

But VC seems different. When Ricky Bobby said “If you ain't first you're last”, he was also talking about venture capital funds. If you can’t get a job at a top VC firm, or get on a path to one, it’s not nearly as good a deal as other industries. It’s harder than ever to join a top firm given how competitive it is but easier than ever to join a Tier 2 or 3 firm given all the new VC capital in the last few years. And given the dispersion data, getting a bigger share of the pie at a less prestigious firm is a risky bet. Getting 5% of 0 is still 0.7

I’m obviously not saying it only makes sense to join Sequoia or that you can’t succeed at a non-name brand firm, especially given how you can build your own deal flow today like never before. Maybe you want to get into venture because it’s a fun job (it clearly can be!) and you don’t care as much about any of this.

My only point is that people should go in with eyes wide open about the math of venture and be much more discerning about where they decide to join. I’ve seen too many smart people who want to enter VC (and even some folks in VC!) that don’t seem to internalize the math sufficiently and are ok joining almost any fund. Picking the right firm is more important than you think and sometimes the answer might be to not join one at all.

There is obviously a different kind of selling you need to do to accumulate and retain assets which is separate from picking great investments. As Matt Levine jokes, “the essential skill of a hedge fund manager is not picking stocks that go up but rather continuing to run a hedge fund.”

I have no hard data on this, so this is based on my anecdotal conversations with VCs and what I’ve read. I’ve never been a VC myself, so feel free to tell me how wrong I am

Technically some definitions of PE include VC but I’m referring to the colloquial use which mainly covers buyout funds

To quote a friend in PE, winning a deal is 80% price, 10% about the partner <> company relationship and 10% other things the PE firm can tout (ex: able to help company expand)

Persistence is the relationship between past and future performance of an investment.

Theoretically this data could be consistent with top funds having better decision making and have nothing to do with better deal flow. But I find it highly unlikely given everything we know about access to deals in the venture industry.

Obviously you can make money on management fees but you don’t get into venture because of the management fees…

Great article - the Morgan Stanley report is a fantastic resource!