Crashing the economy for lower bond yields is a bad idea

A roundup of some unconvincing arguments for tariffs

As someone who used to be a global macro research analyst, scrolling the timeline last week was tough. Many folks in tech, and plenty from outside it too, pushed arguments for the tariffs I found pretty unconvincing. Some people are undoubtedly cheerleading for their team,1 but I'm sure many believe it too.

So putting on my macro hat again, I decided to go through why I don’t buy many of these arguments, the “steelman” I see for tariffs, and thoughts on what happens next.

1) We need rates to go lower to solve our fiscal problems (and they have recently)

I’ve seen this from the All-In crowd as well as some other folks on X. A few reasons this is wrong:

First, it’s not even clear that rates will go sustainably lower due to the tariffs. 10-year yields have already spiked back up, which makes sense if you think foreign holders of US assets are getting spooked by everything happening.

Second, the benefit of lower interest rates in the short term is minimal. The US government has $28T of debt held by the public, but only $9T is set to mature in the next 12 months). 10-year yields were at one point down 50bps from their peak, which would have only amounted to ~$45B of annual interest savings (0.5% * $9T), or ~0.2% of GDP.

That itself is not that much, but that also assumes we are “locking in” this interest rate for a long time. Instead, much of the debt will be rolled over into short-term bills (no more than 12m maturity), so if rates go back up in 3 months, then borrowing costs go back up too.2

Third, and more importantly, the reason tariffs have reduced interest rates is because investors expect them to push the US into a recession if implemented, thereby causing the Fed to lower rates. Whatever small savings you get from lower interest rates are tiny compared to the massive worsening of the deficit you’d have if a recession hit.

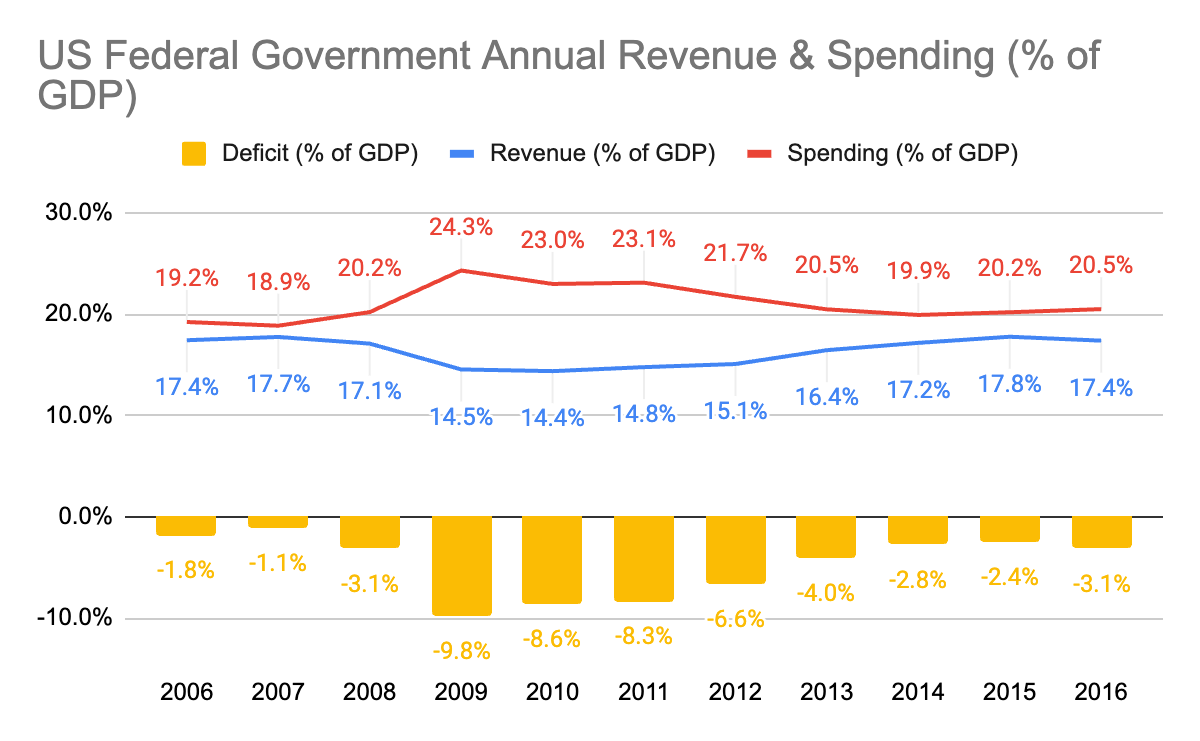

Look at 2008. Government revenue fell off a cliff due to a slowing economy. Stimulus bills and automatic stabilizers pushed spending way up. Revenue fell by over 3% of GDP and spending rose by almost 5% of GDP.

As a result the deficit increased by over 8% of GDP from 2007 to 2009 (remember the slightly lower rates could save us 0.2% of GDP). This all happened despite interest rates falling to 0!

2008 was a particularly severe recession, but creating even a small recession to lower interest rates would make our fiscal situation worse, not better.

2) Tariffs are needed to raise revenue and are just a consumption tax

There’s no denying we have a fiscal problem, with the deficit over 6% of GDP last year. But tariffs are a bad tax to use to raise revenue because they create distortions between domestic and imported goods. A better tax would be a normal sales tax (or better yet a VAT) that taxes all consumption similarly, which is also harder to substitute away from: I can choose to purchase domestic instead of imported goods, but it’s harder to avoid consumption entirely.

Separately, the tariffs don't even raise that much revenue. The Tax Foundation estimates the proposed tariffs (before negotiations to lower them) would only raise $250B a year, or ~0.85% of GDP, compared to last year’s 6% of GDP deficit.

3) Trade has hollowed out the middle class in the last 30 years

This one “feels” right but the data doesn’t support it. The “average American” has not watched their economic lives be destroyed for the last 40 years. As Garett Jones notes, real median family income is up 60% since then. And if anything, inflation has understated the gains.

That doesn’t mean there haven’t been losers to the expansion of free trade, but the impacts are overblown. The biggest reason for the manufacturing employment decline is technological advances, not free trade, and manufacturing output has grown significantly in the last 30 years. The “China Shock” was just not that impactful on employment overall, even if it had an impact on some people in America.

4) We need to bring back manufacturing and the tariffs will help

Pining for the days of manufacturing jobs doesn’t make sense. As you get richer, you move towards service jobs and higher-value manufacturing. Service sector jobs today generally pay more than any manufacturing jobs we’d be bringing back.

But even if you wanted to boost US manufacturing, this is a bad way to do it. These tariffs are not targeted at a product level and 50% of US imports are inputs for domestic manufacturing. Look at Trump’s 2018 steel tariffs which, according to one study, saved some jobs (~1k) in the domestic steel industry but cost the US many more jobs (~75k) in industries that use steel as an input.

And the markets agree. If the tariffs helped US manufacturing, why are major US manufacturing stocks (like Caterpillar) also down big since the announcement?

5) Our trade deficit is unsustainable

Scott Lincicome has done great work on this and the short answer is “No, it’s not.” Our trade deficit (imports > exports) is equally offset by our capital account surplus (investment into US > US investment abroad). The excess dollars we spend on foreign goods are then used by foreigners to buy US assets like bonds, equities, property, and more.

This does mean that we rely on foreigners to fund some of our investments, which poses risks like interest rates rising if foreigners choose to purchase less of our debt at current yields. And there are larger debates about the benefits and costs of the dollar reserve currency status (which drives this) which are for another piece.3 But there’s no reason this current dynamic can’t continue for a long time.

6) The bottom 50% of Americans don’t own stocks and are net debtors, so they benefit from this

The stock market is falling because it expects a recession, which is obviously bad for the bottom 50% (recessions cause job loss!). Bessent says that we need to provide the bottom 50% “some relief” but this would not be it.

The “steelman” for tariffs

There are more I can go through, but I’ll stop there. So what’s the steelman for tariffs? Assuming this isn’t a negotiation tactic to reduce overall tariffs (which I’d be more ok with but seems unlikely),4 I’m largely aligned with Noah Smith that national security is the best argument. We shouldn’t be reliant on adversaries like China for key parts of our supply chain across military and technology needs. We also need some manufacturing base that can be scaled up in a time of war. The US accounts for 0.1% of global shipbuilding and China is >50%.

I’m also sympathetic to arguments about protecting certain types of industries like semiconductors. However, these tariffs are largely not conducive to these goals.

What’s next?

I don’t pretend to know, but I have a few cautionary points:

A 90-day pause doesn’t solve too much (what companies will make decisions based on that?). And even if the tariffs are reversed, uncertainty might permanently remain over the rest of the presidency.

Everyone has a breaking point and the “Trump Put” exists, but it’s probably nowhere close to where we are today.

If we really are getting a recession (which we can still avoid), the market is nowhere near the bottom. People used to buying the dip need to look at how much multiples can compress in a real recession.

I, of course, never suffer from any such biases!

There were suggestions that Bessent could use tariffs to force foreign creditors to swap short-term bills for long-duration bonds that lock in lower rates, but this seems wishful. If we tried this, long-term yields would rise significantly on the back of 1) more supply and 2) countries moving away from USD assets long-term given this type of intervention.

For example, Matt Klein and Michael Pettis’ book on this. I generally think reserve currency status has much larger benefits than costs.

Trump has always been a fan of tariffs and thinks the trade deficit is a “loss.” Even if we negotiate down to a 10% across-the-board tariff, that’d still be a big increase.

Good piece!

Two quick points:

re. China Shock and job losses, we basically switched from manufacturing (manly) to healthcare service work (womanly). They net out, but the cultural impact is not zero. Far from it. It may be a good thing, but composition matters.

re. steelman, intuitively (ala Buffett), trading ownership tomorrow for consumption today, should give one pause. "Hey, we can consume all your stuff today, while tomorrow you'll cash in those IOUs" creates some duration-mismatched incentives. Just because the exchange is happening, doesn't mean it's a *good* exchange.