The IPO Window is Fake

Why more startups can and should go public, even if it means a down round

Oscar Health had the IPO story that every public company fears. After IPOing at a $7bn valuation in early 2021, its stock fell by ~95% and the market valued the company at less than its Series A valuation ($800m) from 2014 . After an impressive turnaround, the stock has bounced back considerably but is still well below its peak valuation.

You’d think after this brutal experience, the cofounder and former CEO Mario Schlosser would regret going public right? In fact, it’s the opposite.

As Schlosser notes, Oscar’s actual fundamentals like revenue and profit are doing much better than their (presumably rosy) pre-IPO projections in early 2021. Since then, they’ve 5xed revenue and went from -18% to +5% net income margins (chart below). It’s been “excruciating” but Schlosser says being public helped them get feedback faster instead of lying to themselves if they stayed private.

Schlosser’s points here don’t just apply to Oscar. More startups should be going public earlier, even if it means a down round, if they match the following three criteria:

Companies that are big enough (ex: valued >$1-3bn)

Companies which have set up the right infrastructure/controls to be a public company (lots of finance/compliance/legal work to do which takes time)

Companies which can’t raise at much better terms from private markets1

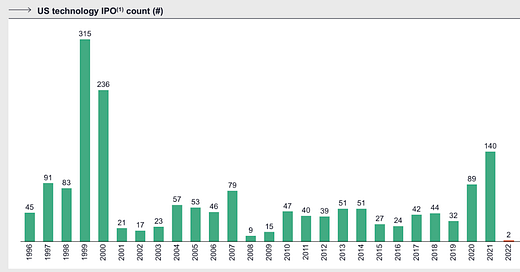

A lot of companies today fit all three criteria and still haven’t gone public (examples: Chime, Brex, Navan, etc.) and the most common reason is the price they'd IPO at is lower than they’d want. Many of them even filed S-1s in the pandemic, meaning they were operationally ready, but have since reversed course. This has resulted in fewer tech companies going public in recent years than at any time in the last 30 years.

There are three main reasons why going public is a good idea for these startups:

It’s good for the long term success of the business

You can’t really time the market (the IPO window is “fake”), so it’s not worth waiting

It’s good for the employees

Going public gives you important feedback about your business

If you care about long-term business success and are trying to come up with the right strategy, there is no better feedback to get than from being public. Right now the feedback is harsh to many founders, and going public would mean valuing the company at a lower valuation than their last private round. Companies are instead choosing to stay private, engage in “turnaround projects” to improve growth/profitability and get their numbers to some arbitrary threshold they’ve deemed necessary to go public.

But too many founders are confusing the comfort of private markets with their wisdom. Staying private doesn’t change what you’re really worth, it just masks it. As Schlosser notes, going public means “you just find out faster how you’re really doing and if you’re private you can lie to yourself for longer.”

Instead of trying to engage in a turnaround project while private, the better option for many companies is to do it while public. Public markets can bring real-time feedback to whatever plans you are conducting and can tell you if you’re on the right track. Even better, this feedback is effectively free! You have thousands of highly paid professionals analyzing your company and putting their money on the line. Contrast that with private investors who are often more likely to fawn to win a deal than provide the right feedback.

Being public obviously means more day to day volatility than if you were private, but I think it’s worth it to get the feedback. It’s this type of feedback that encouraged Oscar’s shift, Meta’s “year of efficiency”, GE’s recent spinoffs, and countless other strategic shifts which lead to long term business improvements (and increased stock prices).

“Get profitable and then IPO” is too simplistic

Too many companies today think they can distill public market feedback into something along the lines of “be profitable.” For example, the CEO of Navan said “you need to be profitable” to be public and implied they are waiting for that to happen before IPOing (note: they filed their S-1 in 2022!).

He’s not wrong that being profitable is more valued today than before, but public markets are forward looking and their feedback much more nuanced than this type of simplistic framework. Instacart seemingly waited to IPO until they showed a small profit, but that did little to prevent a low revenue multiple (~2.5) and big down round at the IPO. Meanwhile, Cloudflare and Samsara still lose money every quarter but trade at 15x revenue. “Get profitable” is not a sufficient strategy to undertake when private and companies are missing on the more nuanced feedback that public markets provide.

Public markets are not too short term focused

A common response I hear is that public markets just don’t understand many private companies’ visions, so going public will put too much pressure on companies to abandon the right long-term plans. Coatue founder Philippe Laffont recently made this point when arguing why companies like OpenAI should not be going public:

“The second [criteria for going public] is: do you have a… break even [business] or path to break even? And… I don't know the specifics of OpenAI but what if you had a billion in revenue but like an enormous cash burn - and by the way that cash burn is really smart. It helps them consolidate as a clear number one. But will the public markets be scared if the cash burn is disproportionate? The private markets, the investors, they know that there's a bit of a winner take all and they might be more patient.”

In most cases, I think this argument is the opposite of the truth. Is it more likely that public markets just “don’t get it” or that this is a self-serving argument by many startups? There is a lot of research and “anecdata” suggesting that public markets can be sufficiently patient and are not particularly short term focused. Examples like Amazon, Tesla, and Netflix show that when companies articulate a clear and credible story about their investments, public markets do not penalize them for it and instead reward them with large multiples.

Even if public markets get it wrong sometimes, I still think the benefits generally outweigh the costs from getting their feedback. The best founders bring an Olympian mindset to company building. If you’re training for the Olympics, would you rather have a trainer which is maybe a little too harsh and demanding on you? Or one which is too nice? As Schlosser notes, you should aspire to be public because it’s “a whole other level of scrutiny and living up to your promises.” More founders should welcome the sometimes harsh but usually helpful feedback public markets provide.

You can’t really time the market (and the IPO window is fake)

Another pushback I’ve heard is “why should companies go public at low valuations when they can wait for markets to improve and their valuation to go back up?” There’s pain and misery that comes with a falling stock price, so if you can avoid it simply by waiting, it’s not a bad idea. Unfortunately, it’s wishful thinking to assume that you can time the market and just wait for your valuation to go back up.

Why? First let’s talk about a concept everyone loves to discuss: the “IPO window”. If you spend more than 60 seconds thinking about it, the idea doesn’t really make any sense.2 The market is obviously always open and there will always be a bank willing to take you public regardless of the so-called “IPO window”. Companies also don’t need to have a $10bn valuation, like Laffont also claims, to find a plethora of buyers of their stock. Just look at all the non-tech IPOs so far in 2024, many of which have much less than a $10bn market cap. The “IPO window” is always open and saying it’s “closed” is really just a euphemism to describe when public markets aren’t valuing your company where you want them to.

The false promise of the “IPO window” is that if you just wait long enough, the window will “open” and you’ll get your promised valuation. But anyone who knows markets knows that’s not how it works. Sometimes markets go back up, but many times they don’t. Valuations for high growth SAAS companies have recovered somewhat in the last year, but fintech valuations are still in the gutter and that’s with the S&P 500 near all-time highs!

All this focus on the exact valuation at the IPO is also counterproductive long term for most tech startups. Do you remember what Google was valued at when it went public? Or Netflix? Or Salesforce? Do you remember if it was a down round or an up round? Whether the stock went up that day? None of this actually matters to the long term success of a company.3

Again, I’ll quote Schlosser here.

The IPO is just a point in time in your company’s life cycle. You can’t really time the market, so the sooner you move past this point in time, the better.

Going public is the right thing to do for employees

Going public is also the right thing to do for your employees and can give you an edge in hiring.

There’s this idea out there that going public in a down round is bad for your employees, but it’s often the reverse. If you last raised at $5bn and you can only IPO at $2bn, staying private doesn’t mean your company is still worth $5bn. It may feel good for the current employees to think it's worth more and I don’t doubt it temporarily helps with company retention.4

But given you can’t just wait for the market to go back up, staying private does a disservice to employees by potentially misleading them about the true value of the company. I think the right thing to do is to give them the liquidity of public equity and let them make the decision of whether to sell or hold onto the stock and hope it goes back up. This is especially true if employees aren’t given the same opportunity as founders to sell secondary in private rounds along the way.5

For employees, shares in a public company are also better than options. Options in later stage companies in particular are often expensive to exercise, can create huge tax bills on illiquid equity, and can put employees in difficult situations when leaving if there’s a short time window to exercise them.6 In an era where a lot of late stage equity is of increasingly unclear value, being public gives you an edge in acquiring talent because your equity is liquid and has more clear value.

A patriotic 🇺🇸 aside: Having more public companies is also good for all tech employees and the country as a whole. Capital misallocation is a big issue, but I think a similarly important and undiscussed issue is labor misallocation. Given private valuations can often be stale, the big problem when companies stay private today is it makes it very hard for tech employees to figure out where they should work! We want engineers spending time building the right products, not playing financial analyst on prospective startups they are joining with limited information.

Celebrating down round IPOs

Why have tech IPOs gone to near zero in the few years if my argument is so strong? I’m not denying the many downsides of going public:

You have to be more careful with communications and deal with compliance/legal costs

You need to air your dirty laundry and reveal more to competitors

The public markets volatility can be distracting

But I think companies are focusing too much on these negatives and not enough on the long term positives. I also think we’ve created a culture which disincentivizes going public. Going public in a down round is seen as a failure. Investors are likely to push the narrative that it’s better to wait for an IPO instead of them having to realize a loss, and the media loves publishing stories about how some companies fall from grace.

We can change this. We can do more to celebrate founders who make the tough decision to go public even if it means a down round, like the founders of Instacart and Klaviyo. Or founders like Oscar’s Schlosser who took a company public, suffered through a big drawdown, but are honest about the values the public markets provided as difficult as the experience was. This piece is my small contribution to the effort.

Thanks to Kasra for his helpful feedback.

If you can get substantially better terms staying private, I do think the value of going public diminishes somewhat. There is still the risk you are being misled about the value of your business (ex: WeWork and Softbank) but I at least understand the rationale more. Many companies today are not in this position though and are facing down rounds in both private and public markets. If you can get $5bn by staying private but $4bn by going public, you should really just go public.

This idea is not a thing in any other market. When the Fed raises rates, do we say the bond issuance window is "closed" because a company wanted to issue at 5% but has to issue at 6%? No, they just issue at the market price and deal with it. The same goes for existing public companies who issue new shares. In fact, most equity issuance historically happens after an IPO. Only 30% of equity issuance dollars in the last 5 years came from IPOs.

The same dynamic happened when I was at Uber during the time of the IPO. There was a ton of press and media scrutiny around the IPO given it was at a disappointing valuation and the stock fell thereafter. Five years later, it’s basically forgotten. No one looking at Uber’s stock cares much at all about the IPO price, nor do most of its employees. Instead, the company is entirely focused on the business performance and the feedback it’s getting in the public markets. And similar to Oscar, public market scrutiny pressured Uber into a business transformation which resulted in their first profitable year in 2023 and a record high stock price recently.

I know there’s a big fear of a public market death spiral where your stock price falls, people leave, it becomes harder to raise capital, your stock price falls further, etc. I think this can happen but 1) this is often just a sped up version of what would happen to the private company anyway and 2) companies, especially great ones, can recover from these drawdowns. Schlosser also notes that turnover eventually stabilized for Oscar even with the stock down.

If companies do stay private, I hope more follow the SpaceX approach. They’ve done tender offers every 6-12 months for the last ~10 years, giving employees (and investors!) liquidity and a more consistent price for how much their equity is worth. Not every private company can do this (you need to be quite big), but the more that can the better.

It’s common for companies to require you to exercise your options within 90 days of leaving or you forfeit your them.